Episode 2: Life Everlasting

Download MP3The slaves that they brought in call it life may last, but they recognize the plant. Yeah, because they came from West Africa and the coastline and everything, so they know about the tides and fishing for mullet and different plants that was on the island, they were used to seeing. So when they came and they saw this, it's old, life may last.

Courtney:Hi. I'm Courtney McGill, and you're listening to Griot's Garden, a podcast that explores the intersection between people, plants, and culture through conversations with descendants of Sapelo Island's Gullah Geechee community. Join us as we share stories of how native plants have played an important role in their lives. We couldn't begin this episode without remembering Miss Cornelia Walker Bailey. Miss Cornelia was a storyteller, writer, historian and activist for the preservation of Sapelo until her passing in 2017.

Courtney:Her roots on the island could be traced back over 200 years. She was dedicated to uplifting Gullah Geechee culture and used her voice to honor her ancestors in the Sapelo way of life. In this episode, we'll hear from her eldest son, Stanley Walker.

Stanley:My name is Stanley Walker. I'm 7th generation Sapelonian. I was born on Sapelo Island by the same midwife that brought my mom into the world.

Courtney:Stanley is a man of many skills, including weaving sead nets, which is a type of fishing net used to catch fish along the shoreline. For many years, he could be found at Sapelo Island's annual Cultural Day Festival doing live demonstrations of his netmaking techniques. He is also well versed in the history and use of native plants by the Gullah Geechee community on Sapelo. This knowledge wasn't learned overnight. It was passed down through generations.

Courtney:Stanley's link to the past is strong. He owes much of his craft to those who came before him. Miss Cornelia was a significant figure in his lineage. Not only was she a keeper of culture and tradition, she was a driving force behind preserving heritage and helping to instill pride among the islanders and descendants. Cornelia Walker Bailey.

Stanley:Well, she believed in the island and she did a lot of fighting to preserve the land and keep the heritage going and help put Sapelo on the map and brought awareness, make people proud of it being a Geechee and a Gullah because a lot of people like, I'm not Geechee, I'm not Gullah. So she kinda brought it out and was like, hey, there's nothing to be ashamed of, you know.

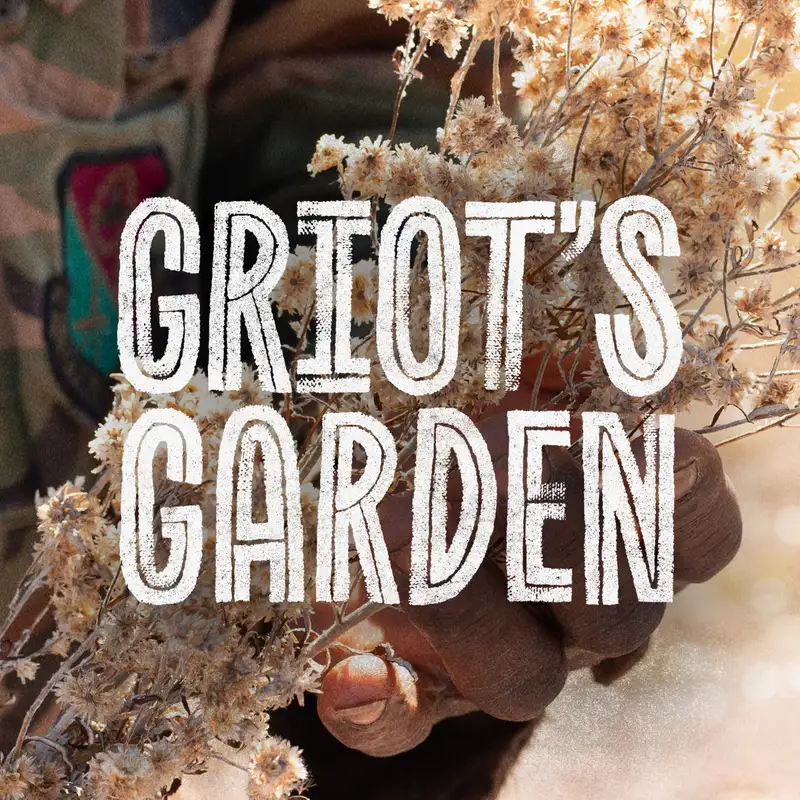

Courtney:In her memoir, God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man, miss Cornelia offers readers an in-depth look into her memories of life on Sapelo. The book explores themes of community and family and touches on her connection to the natural world, such as the woods and waterways. In one chapter of the book, she shares her recollections of the use of life everlasting, a plant commonly brewed into a tea to treat cold symptoms. In the book, she says: Papa would come across life everlasting growing in the woods, and he would bring home these huge bunches of it tied to his knapsack and hang them outside in the cornhouse to dry. Life everlasting's got tiny little leaves that turn kinda silver gray in the fall when it's ready for you to pick it, and little white blossoms on the top, so when he wanted some tea, he'd go out back, break a piece, and boil it up.

Courtney:Cornelia goes on to refer to life everlasting as a poor man's Lipton with the ability to get you up and going, just as good as store bought tea. As a child, she found herself pondering on its name, life everlasting. Because true to the notion, most folks that she knew to drink it went on to live long lives, including her uncle Shad, who lived to be over 100. Like his mother, Stanley was introduced to the use of life everlasting and other native plants early in his childhood.

Stanley:I grew up with my grandparents, which, you know, they didn't hardly believe in doctors, so I got chance to test the life everlasting and other remedies that they had going on. I can kinda help y'all out, tell you what not to take and what to take.

Courtney:When enslaved West Africans were brought to the shores of what is now known as the Gullah Geechee Corridor, extending from Wilmington, North Carolina to St. Augustine, Florida, they found an unfamiliar and strange land. But they also found similarities to their native lands along the coastal landscapes. This allowed them the ability to retain the tradition of relying on nature and to strengthen their chances of survival under the harsh realities of American slavery.

Stanley:The slaves that they brought in call it life may last because they recognize the plant. Yeah. Because they came from West Africa and the coastline and everything, so they know about the tides and fishing for mullet and different plants that was on the island, they were used to seeing. So when they came and they saw this, it's old, life may last. On Sapelo, we call it life everlasting.

Stanley:And you go to Carolina, some parts of the low country of the Carolina, they call it low country everlasting. You look it up in the book and you say life everlasting, it say rabbit tobacco. But if you put low country everlasting, it'll bring up all the properties and stuff like this, and what people use it for.

Courtney:Life everlasting has been used in many countries for 100 of years as an herbal medicine to treat colds and sore throats, a tight chest, a stuffy head, a down spirit, or as a general tonic. It has specific identifiers to note when looking for it out in the wild. While it's easiest to find when it's dead and dried out, Stanley has mastered the ability to find it at any stage.

Stanley:Well, in the wild while it's green, it will have beautiful green limbs, leaves coming off the stem, and the bronze on it will be green too. So a lot of people never learned how to fire while it's green, they learned how to do it while it's dried out, so I can do it both ways. When it dries, the leaves will turn brown, and under the bottom be kinda creche like, and the blooms will turn white. Look like little dry flowers.

Courtney:Although the plant is widely used, it takes an expert like Stanley to find the plant during the growing season.

Stanley:Yeah. You mostly find them in open fields around pine forests. Yeah. And once you recognize it one time, you have your eyes, like, oh, here goes life everlasting. A lot of people still drink it, but they don't know how to find it.

Stanley:I had this lady call me, she said, I need some life everlasting. I said, there's some right by your house. She said, no. It's not. I went over, walked to a mailbox, picked up a big bundle.

Courtney:The plant becomes ready to pick in the late summer or fall, just ahead of cold and flu season.

Stanley:Well, if you pick it green, you would you would take it, you would pull the whole plant up, shake the dirt off the roof, and you tie it upside down so all the properties can go through the plaza drying. And people will gather during the summer and let it dry all summer and have it for the winter. But you just break it up and just put it in a teapot and let it steep. Don't worry, you will smell it. I had to let you know.

Stanley:You will smell it would pull out a smell and you're like, okay. I think it's ready.

Courtney:In Way Back Lowcountry, Life Everlasting by Michelle Roldan Shaw, she states, the Cherokees and other southeastern indigenous tribes called it rabbit tobacco, and early travelers like botanist John Bartram and ethnographer James Mooney noted its sacred importance. The plant was smoked, used in sweat lodges, junk as a decoction, applied topically to wounds, and placed around the home to ward off evil spirits and witchcraft. Early settlers caught on and started making little pillows stuffed with life everlasting to treat consumption, while modern enthusiasts have claimed to cure asthma by the same method. Within the last several 100 years, Sapelo Island West African ancestors and descendants recognized the value and use of the plant. While Stanley acknowledges the power of the plant, he remembers putting up a fight against drinking it when he was a child.

Stanley:Oh, I was I was young and I remember my grandparents gave into me because I had a bad cold and it was hard for me to sleep at night. The cold was kicking my butt. So they made some. See my grandfather, he believed in everything bitter, he gave me that and I spit it up. I spit it up.

Stanley:I refused to open my mouth and he told me, said boy, if you open your mouth I'm a tell you so and so. So I had to drink it and I tried not, if I was sick I tried not to tell them because I didn't want no more that.

Courtney:Despite his early memories, Stanley continued to experiment and use the plant later in his childhood and teens.

Stanley:But for us, we use it as herbal medicine. But the life everlasting, you can smoke it. I don't know what the outcome might be. You might not remember your name come to or you care. You know, when you're young, you didn't know no better.

Courtney:Stanley has since found new ways to enjoy life everlasting. Although he still finds the bitter or barefoot taste challenging, the plant continues to provide him with healing and restoration.

Stanley:The old people just say drink it barefoot. That means bitter. I drunk some I made some last night, but I can never drink it barefoot. I tried it once. I wouldn't do it to my worst enemy.

Stanley:It's bitter, it's real bitter. And you can drink it barefoot, which means bitter, you can do like I do. A little honey, you can any kind of whiskey of your choice. If you're not a liquor drinker, you're not drinking whiskey then, you got medicine. You can put moonshine if you can find it, vodka, gin, and that just enhance and you drink it before you go to bed.

Stanley:And you cover up up because it's gonna make you sweat. So you try to stay covered up and it will work that cold out you and make you feel better. But it's a natural sedative so it would help you to sleep, cause you to sweat if you have a cold and stuff like that, and I have to sweat it out. So a lot of people just drink it just to help them relax.

Courtney:As a father and grandfather, Stanley has occasionally used the threat of life everlasting to keep rambunctious children in line.

Stanley:Yes. I have given it to my kids, and if I mention it now, they would take off a run. I gave it to some of my grands. They didn't like it. They were like, and so a lot of times if I wanted them to be good, I said I'm gonna blow up some life everlasting, that's what you're gonna drink tonight, you have no more problems.

Stanley:So y'all gonna have to try it.

Courtney:Oh, no. You're not selling it for me yet.

Stanley:It's not as bad as I make it say.

Courtney:When I was growing up on the island, it was a common sight to see my stepfather, Larry, standing over the stove, brewing him a little pot of life everlasting. I was a preteen and so engulfed in my inner world that I never paid close attention. I never took the time to try it myself or stand with him to take notes on the process, but what I do remember is how it seemed to be one of those things he didn't have to think too hard about. Watching him make it was like watching water flow. When he wanted some tea, he knew exactly where to find it and how to make it just right.

Courtney:I hope to one day relearn the beautiful ways of life I was exposed to all those years, but this time with fresh eyes and a deeper understanding of the rich and healing roots from which it all stems. This podcast is brought to you by University of Georgia Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. Supplemental materials about the native plants discussed in this episode can be found at gacost.uga.eduforward/podcast.